новости и аналитика для форекс

Взрывные новости Forex, глубокая аналитика рынка и точные прогнозы — всё для успешной торговли! Получи преимущество, читай нас!

Новости и аналитика для Форекс⁚ Путеводитель для трейдера

Успешная торговля на Форекс невозможна без понимания влияния новостей и аналитики․ Это ваш ключ к предсказанию рыночных движений и принятию взвешенных решений․ Грамотный анализ позволит минимизировать риски и максимизировать прибыль․ Освойте искусство чтения рыночных сигналов и управляйте своим капиталом эффективно․ Начните с изучения основных экономических показателей и их влияния на валютные пары․ Помните‚ что постоянное обучение – залог успеха на Форекс!

Основные источники новостей для Форекс

Для успешного трейдинга на Форекс критически важно получать достоверную и своевременную информацию․ К счастью‚ сегодня доступно множество надежных источников новостей‚ позволяющих быть в курсе событий‚ влияющих на валютный рынок․ В первую очередь‚ рекомендуется следить за новостными лентами ведущих мировых информационных агентств‚ таких как Reuters‚ Bloomberg и Associated Press․ Эти агентства оперативно публикуют заявления центральных банков‚ данные о ВВП‚ инфляции‚ безработице и других важных макроэкономических показателях․ Обращайте внимание на время публикации данных – часто именно в эти моменты наблюдается повышенная волатильность․

Помимо глобальных агентств‚ следует использовать специализированные финансовые порталы и сайты‚ предоставляющие аналитику и комментарии к новостям․ Многие брокеры предлагают своим клиентам доступ к экономическим календарям‚ в которых указаны даты и время выхода важных экономических показателей․ Это позволит вам заранее подготовиться к возможным колебаниям рынка․ Не забывайте о социальных медиа‚ хотя следует относиться к информации из этих источников с осторожностью‚ верифицируя ее в более надежных источниках․ Важно обращать внимание не только на сами новости‚ но и на реакцию рынка на эти новости․ Изучайте исторические данные‚ чтобы понять‚ как рынок реагировал на подобные события в прошлом․ Это поможет вам более точно предсказывать будущее поведение цен․

В целом‚ использование разнообразных источников новостей — ключ к получению полной картины рыночной ситуации․ Комбинируя данные из нескольких источников‚ вы сможете сформировать более объективное мнение и принять более информированные торговые решения․ Помните‚ что своевременность и точность информации имеют критически важное значение для успеха на Форекс․

Анализ новостей⁚ выявление ключевых сигналов

Получение новостей – это лишь первый шаг․ Ключ к успеху лежит в умении анализировать эти новости и выявлять ключевые сигналы‚ которые предсказывают будущие движения рынка․ Не каждая новость оказывает значительное влияние на валютные пары․ Важно научиться отличать действительно важные события от второстепенных․ Обращайте внимание на контекст новости⁚ какие факторы привели к этому событию‚ каковы его возможные последствия для экономики и валютного курса? Не достаточно просто прочитать заголовок – нужно вникнуть в суть события‚ изучить детали и проанализировать реакцию рынка․

Обращайте внимание на реакцию рынка на выход новостей․ Быстрая и резкая изменчивость цен может указывать на важность события․ Однако‚ не всегда немедленная реакция является показателем долгосрочного влияния․ Иногда рынок может сначала продемонстрировать краткосрочную реакцию‚ а затем вернуться к предыдущим уровням․ Поэтому важно следить за динамикой цен в течение нескольких часов или даже дней после выхода новостей․

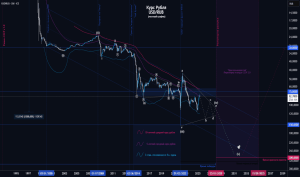

Научитесь использовать технический анализ в сочетании с фундаментальным․ Технический анализ поможет вам определить уровни поддержки и сопротивления‚ а также выявлять паттерны цен‚ которые могут подтвердить или опровергнуть сигналы‚ полученные из фундаментального анализа․ Например‚ прорыв уровня сопротивления после выхода позитивных новостей может служить сильным сигналом для покупки․ Не бойтесь использовать индикаторы технического анализа‚ но помните‚ что они являются лишь дополнительными инструментами‚ а не гарантией успеха․

И‚ наконец‚ не забывайте о психологии рынка․ Реакция рынка на одинаковые новости может быть разной в разное время․ Это связано с общей рыночной сентиментностью и ожиданиями инвесторов․ Учитывайте эти факторы при анализе новостей и принятии торговых решений․ Постоянная практика и наблюдение за рыночной динамикой помогут вам развить необходимые навыки для успешного анализа новостей и выявления ключевых сигналов․

Использование аналитики для принятия торговых решений

Анализ новостей и рыночной ситуации – это не самоцель․ Его конечная цель – помочь вам принимать более обоснованные и прибыльные торговые решения․ Не стоит воспринимать аналитику как единственный источник истины – это лишь инструмент‚ который нужно умело использовать․ Важно понимать‚ что даже самый тщательный анализ не гарантирует 100% успеха‚ поскольку рынок подвержен множеству неопределенных факторов․ Ключ к успеху – это умение интегрировать аналитические данные в вашу торговую стратегию и учитывать риск․

После анализа новостей и выявления ключевых сигналов‚ необходимо определить вашу торговую позицию․ Будете ли вы покупать или продавать валютную пару? Основываясь на полученной информации‚ определите целевые уровни цены‚ при достижении которых вы закроете сделку с прибылью․ Не забудьте также определить стоп-лосс – уровень цены‚ при достижении которого вы закроете сделку с убытком‚ чтобы ограничить потенциальные потери․

Важно помнить‚ что анализ – это не только про поиск сигналов к покупке или продаже․ Не менее важно уметь определять моменты‚ когда лучше воздержаться от торговли․ В периоды высокой волатильности и неопределенности лучше подождать более спокойного времени‚ чтобы избежать ненужных рисков․ Умение «ничего не делать» также является важной частью успешной торговли․ Не стремитесь к постоянному заключению сделок – сосредоточьтесь на качественных сигналах и терпеливо ждите подходящего момента․

Используйте различные инструменты для анализа и подтверждения своих предположений․ Например‚ сопоставляйте данные фундаментального анализа с техническими индикаторами․ Не полагайтесь только на один источник информации․ Проверяйте данные из нескольких источников‚ чтобы получить более полную картину рыночной ситуации․ Помните‚ что успешная торговля требует системного подхода и постоянного самосовершенствования․ Регулярно анализируйте свои торговые решения‚ ищите ошибки и корректируйте свою стратегию с учетом полученного опыта․